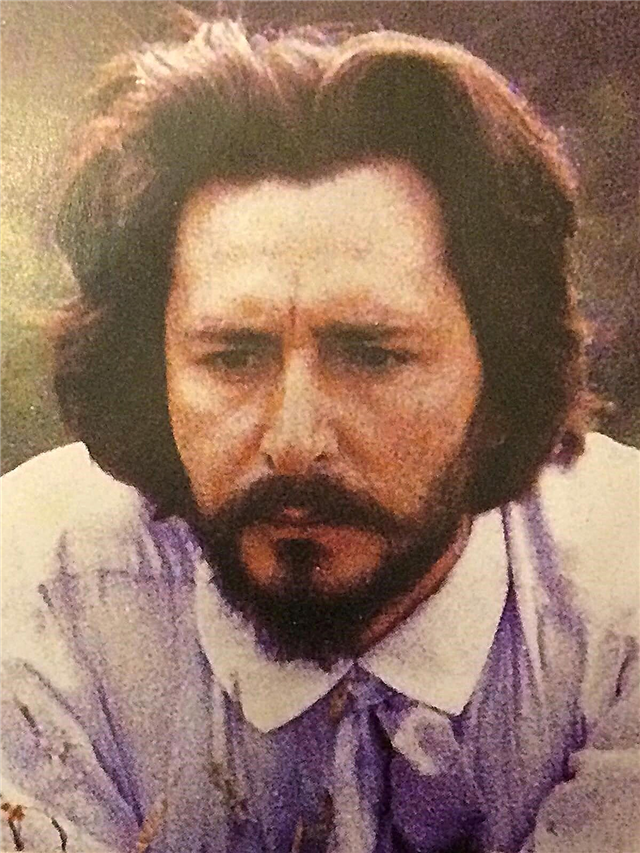

By the end of summer, the parents of ten-year-old Luzhin finally decide to inform their son that after returning from the village to Petersburg he will go to school. Fearing the impending change in his life, little Luzhin, before the train arrives, escapes from the station back to the estate and hides in the attic, where, among other unapproachable things, he sees a chessboard with a crack. A boy is found, and a black-bearded man carries him from the attic to the stroller.

Luzhin Sr. wrote books, in them constantly flashed the image of a blond boy who became a violinist or painter. He often thought about what might come out of his son, whose remarkableness was undeniable, but unsolved. And the father hoped that his son’s abilities would be revealed at school, especially famous for his attentiveness to the so-called “internal” life of his students. But a month later, the father heard cool words from the teacher proving that his son was understood at school even less than he did: “The boy certainly has abilities, but there is some lethargy.”

At breaks, Luzhin does not participate in general childish games and always sits alone. In addition, peers find it strange fun to laugh at Luzhin about their father’s books, calling him by the name of one of Antosha’s heroes. When at home parents pester their son with questions about the school, the terrible thing happens: he, like a madman, knocks down a cup and saucer on a table.

Only in April the day comes for the boy when he has a hobby, on which his whole life is doomed to focus. At a musical evening, a bored aunt, a second cousin of his mother, gives him the simplest lesson in playing chess.

After a few days at school, Luzhin observes a chess game of classmates and feels that somehow he understands the game better than the players, although he does not yet know all its rules.

Luzhin begins to skip classes - instead of school, he goes to his aunt to play chess. So the week goes by. The teacher calls home to find out what is wrong with him. Father is on the phone. Shocked parents require an explanation from their son. He’s bored of saying anything, he yawns while listening to his father’s instructive speech. The boy is sent to his room. Mother weeps and says that her father and son are deceiving her. The father thinks sadly about how difficult it is to fulfill a duty, not to go wherever he is drawn uncontrollably, and then these oddities with his son ...

Luzhin beats the old man, who often comes to his aunt with flowers. For the first time faced with such early abilities, the old man prophesies to the boy: "Go far." He explains the simple system of notation, and Luzhin, without figures and a blackboard, can already play the parts given in the magazine, like a musician reading a score.

Once a father, after explaining to his mother about his long absence (she suspects him of infidelity), invites his son to sit with him and play, for example, chess. Luzhin wins four games against his father and at the very beginning of the last one comments on one move with a non-childish voice: “Worst answer. Chigorin advises taking a pawn. ” After his departure, the father sits thinking - his son’s passion for chess amazes him. “In vain she encouraged him,” he thinks of his aunt and immediately recalls with anguish his explanations with his wife ...

The next day, the father brings a doctor who plays better than him, but the doctor also loses to his son party after party. And from that time on, the passion for chess closes the rest of the world for Luzhin. After one club performance, a photograph of Luzhin appears in the capital’s magazine. He refuses to attend school. He is being asked for a week. Everything is decided by itself. When Luzhin runs away from his aunt’s house, he meets her in mourning: “Your old partner has died. Come with me. ” Luzhin runs away and does not remember if he saw in the tomb of a dead old man who had once beaten Chigorin — pictures of his outer life flicker in his mind, turning into nonsense. After a long illness, his parents take him abroad. Mother returns to Russia earlier, alone. Once Luzhin sees his father in the company of a lady - and is very surprised that this lady is his aunt from St. Petersburg. And after a few days they receive a telegram about the death of their mother.

Luzhin plays in all the major cities of Russia and Europe with the best chess players. He is accompanied by his father and Mr. Valentinov, who is involved in arranging tournaments. A war is passing, a revolution that entailed a legal expulsion abroad. In the twenty-eighth year, sitting in a Berlin coffee house, his father suddenly returns to the idea of a story about a brilliant chess player who is supposed to die young. Prior to this, endless trips for his son did not make it possible to realize this plan, and now Luzhin Sr. thinks he is ready for work. But the book, thought out to the smallest detail, is not written, although the author presents it, already finished, in his hands. After one of the out-of-town walks, getting wet in the rain, his father falls ill and dies.

Luzhin continues tournaments around the world. He plays with brilliance, gives sessions and is close to playing with the champion. At one of the resorts where he lives before the Berlin tournament, he meets his future wife, the only daughter of Russian immigrants. Despite Luzhin's insecurity before the circumstances of life and outward clumsiness, the girl guesses in him the closed, secret artistry, which she attributes to the properties of a genius. They become husband and wife, a strange couple in the eyes of everyone around. At the tournament, Luzhin, ahead of everyone, meets with his longtime rival Italian Turati. The game is interrupted in a draw. Overvoltage Luzhin is seriously ill. The wife arranges her life in such a way that no reminder of chess bothers Luzhin, but no one can change his sense of self, woven from chess images and pictures of the outside world. Long-lost Valentinov is calling on the phone, and his wife is trying to prevent this person from meeting Luzhin, referring to his illness. Several times, the wife reminds Luzhin that it is time to visit the grave of his father. They plan to do this soon.

Luzhin’s inflamed brain is busy solving an unfinished party with Turati. Luzhin is exhausted by his condition; he cannot be freed even for a moment from people, from himself, from his thoughts, which are repeated in him, like once made moves. Repetition - in memories, chess combinations, flickering faces of people - becomes for Luzhin the most painful phenomenon. He "wanders about the horror of the inevitability of the next repetition" and comes up with a defense against a mysterious enemy. The main method of defense is to voluntarily, deliberately, perform some ridiculous, unexpected action that falls outside the general regularity of life, and thus confuse the combination of moves conceived by the enemy.

Accompanying his wife and mother-in-law on shopping, Luzhin comes up with an excuse (visiting a dentist) to leave them. “A little maneuver,” he grins in a taxi, stops the car and walks. It seems to Luzhin that he had already done all this once. He enters a store that suddenly turns out to be a women's hairdresser, in order to avoid a complete repetition with this unexpected move. Valentinov is waiting at his house, offering Luzhin to star in a film about a chess player in which real grandmasters participate. Luzhin feels that cinema is an excuse for a repetition trap in which the next move is clear ... "But this move will not be made."

He returns home, with a concentrated and solemn expression, quickly walks around the rooms, accompanied by a crying wife, stops in front of her, puts out the contents of his pockets, kisses her hands and says: “The only way out. Need to get out of the game. " "We will play?" - the wife asks. The guests are about to arrive. Luzhin is locked in the bathroom. He breaks the window and crawls into the frame with difficulty. It remains only to let go of what he holds on to - and is saved. They knock on the door, the wife’s voice is clearly heard from the next bedroom window: “Luzhin, Luzhin”. The abyss beneath him splits into pale and dark squares, and he lets go of his hands.

The door was knocked out. "Alexander Ivanovich, Alexander Ivanovich?" A few voices roared.

But there was no Alexander Ivanovich.